you're thinking about climate change solutions all wrong, say Indigenous leaders

I put together this breakdown of some intriguing concepts front-and-center for Indigenous activists and leaders at the world’s most important (and never quite effective enough) climate conference. I guess that’s why I still bother keeping a website after all these years!

So… I was asked to crank out a simple, 160-word section memo summarizing Indigenous-presented climate innovations at COP30. But the topic was so inherently vast and deeply compelling that my time management on my part of the project quickly spun out of control.

I ended up spending hours sifting through advocacy papers, pavilion programs, and NGO reports; and it seemed such a shame to leave all of what I found on the cutting room floor.

Instead, I put together this breakdown of some intriguing concepts front-and-center for Indigenous activists and leaders at the world’s most important (and never quite effective enough) climate conference. I guess that’s why I still bother keeping a website after all these years!

Happy Thanksgiving, and here’s what I saw happening (from afar) in Belém.

The First Really Indigenous COP

This year, COP30 had representatives from 198 nations and tens of thousands of attendees across 12 days in November. More importantly for the theme of this newsletter, it was supposed to be the COP that actually centered indigenous parties at the forefront in creating global climate solutions. And, by the numbers, it did set records for indigenous participation & initiatives: An estimated 3000 representatives were in Belém, including 900 delegates officially participating in debates.

Unsurprisingly, considering it took place literally in the Amazon, the main organizers at the table have been Amazonian tribes, and a lot of what was announced were very Brazil-focused, including:

- Brazil’s demarcation of 10 new Indigenous lands, covering almost 1000 square meters.

- The launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility, which received an initial capitalization of around $5 billion that “rewards countries for maintaining forest cover and delivering global benefits like carbon storage, biodiversity, clean water, and climate resilience. “ At least 20% of payments are set to flow directly to Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

- Not for nothing, Brazil had very recently established its first Ministry for Indigenous Peoples, with Indigenous activist Sônia Guajajara appointed as the first Minister. She was a major voice in a lot of the negotiations.

But many, many others showed up too, representing peoples from Africa, Asia and even here in the United States (the only Americans you couldn’t find in attendance — our actual elected leaders). And it’s been a long journey for them to be recognized at global talks for climate change.

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the first treaty to confront climate change, didn’t mention indigenous peoples at all. It took until 2008 for the International Indigenous People’s Forum on Climate Change — their main representative group — to be formed as part of the UNFCCC, and their proposals were largely ignored at the 2010 COP in Cancun. All its events were relegated to COP’s green zone, meant for unofficial “civil society spaces” until 2021’s COP in Glasgow. For the first time, the reps for all global indigenous peoples were allowed to participate in actual official country-to-country negotiations with actual world leaders.

Since then, they’ve been increasingly loud voices fighting for biodiversity, for rigorous human rights standards and a just energy transition, and against “false solutions” like “carbon markets” and “geoengineering.” That’s particularly relevant to the part of the poster I covered…

Not Your G20’s Ideas

Because if you want to hear the hottest of anti-capitalist takes on what the world should be doing about climate change, you’ll probably hear it first from Indigenous activist groups. My part of the group assignment was focused on “Innovative Solutions,” and I got a little deep in the weeds in the topic when I realized that some of the most publicized interventions that were supposed to be inclusive of Indigenous people were barely being talked about by the indigenous groups themselves. For instance, the Bioeconomy Challenge.

On paper, the concept sounds like the perfect antidote to the very capitalism being critiqued: a shift from industrial degradation toward restoring ecosystems via a “sociobioeconomy” that fosters fair growth. The three year initiative is supposed to “build the foundations” for a global system that also has a special call out amongst its 10 High-Level principles to “uphold the rights of all people, including Indigenous Peoples and members of local communities.”

However, the silence from the ground makes sense when you realize the concept’s vagueness is a potential trap. Experts fear it is becoming a loophole for agribusiness to greenwash operations and secure subsidies while continuing to violate Indigenous rights, forcing us to critically interrogate who actually gets to define “restoration.”

Despite that skepticism, the institutional machinery is moving fast to implement scalable solutions by 2028. While stakeholders are finally acknowledging that nature’s value has been underestimated simply because “the forest doesn’t issue invoices,” a glaring disconnect remains. The Indigenous communities supposedly driving this work often lack access to capital because conservation isn't deemed commercially “competitive.”

In fact, looking at the solutions Indigenous groups were putting forward — or at least the ones I could read about through the IIPFCC’s Pavilion program this year — the problem lies directly in the fact that global pacts are insufficient without correcting the financial infrastructure to ensure resources actually materialize for the people most skeptical of them.

So what was more front-and-center for Indigenous groups?

The Rights of Nature

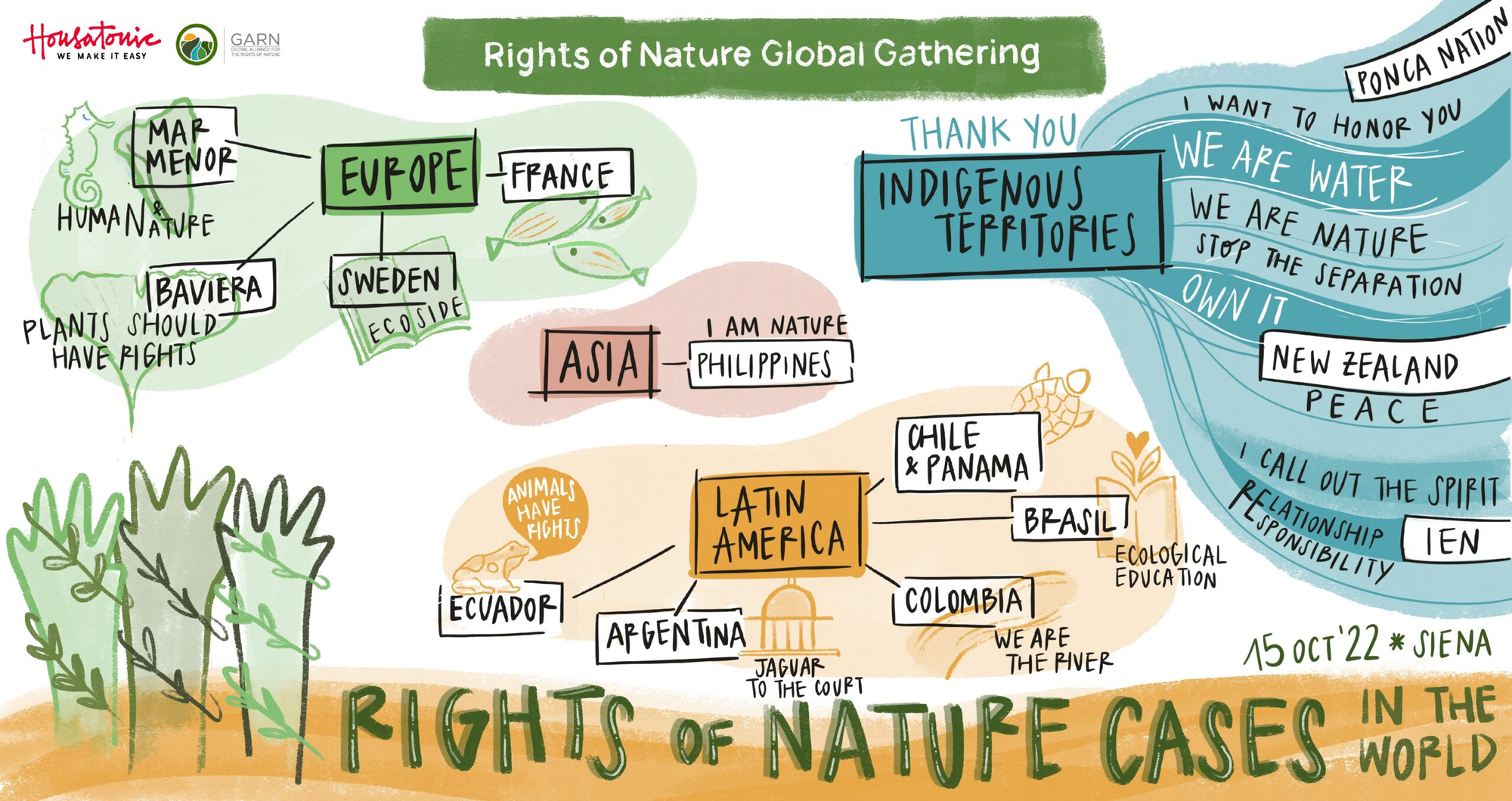

High on that list is the Rights of Nature (RoN) framework, which proposes a fundamental paradigm shift away from a “colonialist” worldview that treats the planet as a resource warehouse. Instead of management, The Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (GARN) calls for a structural revision of our legal and ethical systems to recognize ecosystems as rights-bearing entities with the inherent right to exist, thrive, and regenerate. This approach seeks to replace extractive logic with principles of respect, reciprocity, and interdependence.

This framework stands in direct opposition to the financial mechanisms currently dominating the climate discourse. GARN issues a stark warning against the financialization of Nature, labeling initiatives like carbon markets and the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) as “false solutions”. The argument is that we cannot solve a crisis caused by commodification by commodifying nature further; treating forests as financial assets merely perpetuates colonial patterns of control while failing to address the root causes of ecological breakdown.

Instead of market-driven fixes, the RoN framework demands a transition from control to coexistence. It requires treating Nature as a subject with agency rather than an object for profit. Practically, this entails establishing binding obligations to respect Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and adopting governance models that center ecological integrity, recognizing that human rights are indivisible from the rights of the biospheres we depend upon.

To operationalize this at COP30, GARN highlighted two emblematic initiatives: recognizing the Rights of the Amazon and the Rights of Antarctica. GARN’s position is that these are critical living entities that regulate planetary equilibrium, and granting them legal rights would force a redesign of policy that embeds care and responsibility into its structure, ensuring these biomes are protected for their inherent value before irreversible tipping points are reached.

That through-line of “de-capitalization” was very much continued in some of the other solutions they discussed, such as:

Indigenous-Led Funding

Did you know there was an option to give funding directly to the people stewarding the land? There were at least four main pavilion in the main Blue Zone talks about the concept of Indigenous-Led Funding (ILFs), which redefine philanthropy by prioritizing the 5Rs — respect, relationships, responsibility, reciprocity, and redistribution — over control.

The argument is that conventional philanthropy often perpetuates colonial mindsets, ignoring the historical reality that much of the wealth that funds private foundations originated from the exploitation and appropriation of Indigenous lands and resources. Currently, than 0.6% of global philanthropy is identified as beneficial to Indigenous Peoples, and only 33% of that figure goes directly to Indigenous entities. ILFs contend that conventional processes are excessively bureaucratic, complex, and driven by external metrics, which excludes the most impactful grassroots initiatives.

And while it sounds kind of woo woo and like a pathway that’s easily corruptible, the funds brought forth several examples of funds that have already been doing a great job with their own governance model. Examples include the Podáali Fund in the Brazilian Amazon—a 100% Indigenous-managed mechanism mobilizing resources across nine states; Fundo Rio Negro defending territorial rights, and the Fonds Territorial du REPALEAC fighting to save the Congo Basin forests.

The ask at COP30 was loud: direct access to climate finance. The Amazonía en Peligro! event pushed for the Amazon for Life Fund to be recognized as a pioneer for direct co-governance, demanding recognition as legitimate financial actors in the Paris Agreement. Basically, stop treating them like charity cases and start treating them like expert partners who need long-term, flexible funding, not short-term grants with mountains of paperwork.

Knowing the deep trust issues of charitable donors, and the risk bias of institutional investors, it’s surprising to me that any of this concept has gotten off the ground at all. But similar to the more “officially debated” calls on the UN floor for a trillion dollars of investment into a climate Loss & Damage fund, I suppose there needs to be people on the fringes reminding everyone that inaction is also an action, and we already know inaction = bad outcomes.

A Rights-Based Just Energy Transition

Another way nature/human rights and rethinking financial structures intersected was in Indigenous suggestions for how to decarbonize our energy systems, mitigating climate change, in a more empowering fashion. The push to electrify the world is necessary, but it has created a brutal collision point by demanding huge volumes of critical minerals for batteries and solar panels. Since the vast majority of these deposits sit on or near Indigenous territories, the energy transition risks becoming a new wave of colonial resource extraction, simply swapping fossil fuels for lithium and copper.

Entities like the SIRGE coalition demanded a structural change to halt this cycle, arguing that if we fight climate change by repeating the violence of historical mining, we are just exchanging one environmental cost and human rights violation for another. They called for moratoriums on extraction in and near Indigenous territories and insisted that Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) must be recognized—not just as a consultation, but as a mechanism providing veto power over projects that impact their land. They are demanded that Loss and Damage funds support Indigenous-led monitoring and transition planning, ensuring resources aren't simply channeled back to the governments and corporations responsible for the original harm and ongoing violence.

On the generation side, organizations like the Right Energy Partnership (REP) are actively working to support Indigenous-led renewable energy systems. Their work focuses on micro-solutions like solar, micro-hydro, and wind, which are built to strengthen local self-determination while providing clean energy access. REP’s mission is to secure the necessary financial and technical support to scale up these community-owned systems, rather than waiting for large, extractive national grids to arrive.

This Indigenous-led conversation is fundamentally different from the one often heard in the main COP halls. Mainstream pledges often ignore land tenure and consent as operational details. The Indigenous position, conversely, frames justice, land tenure, and FPIC as absolute non-negotiable preconditions for any successful decarbonization pathway. It’s the difference between funding the CEO of a lithium mine and funding a community building their own solar microgrid: it forces the moral compass to call out the hypocrisy of fighting climate change by perpetuating colonial extractivism.

In that vein, there was also a call for more Indigenous voices to be represented in national commitments, specifically through Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Circling back to the Rights of Nature (RoN) framework, Indigenous groups expressed the need to ground national climate planning in ecological integrity rather than the extractive growth models currently favored.

While those were the three that most stuck out to me as particularly intriguing concepts trying to gain more traction in the wider climate space, they were by no means the only ideas Indigenous people were putting forward. I should note that there was a lot of discussion around women’s leadership, oft-ignored Indigenous wisdom and education, and calls for protecting the safety of environmental defenders, because they are still being exiled, disappeared and murdered at alarming rates.

Ultimately, COP30 felt historic, but the overall mood left many tribes feeling visible but not empowered. Despite the growing “official” recognition, Indigenous groups still felt excluded from the main decision-making halls, which is probably why there were two major protests that interrupted the proceedings.

It was a frustrating juxtaposition: celebrating a process that allowed 900 delegates to officially participate in debates, while knowing that the structural issues of colonial financial control remain intact. Still, considering how little the Indigenous position was taken seriously before, and knowing their resilience in the face of hundreds of years of oppression, there is genuine hope regarding their continued presence, amplified recognition, and their growing capacity to communicate and mobilize globally against extractive logic.